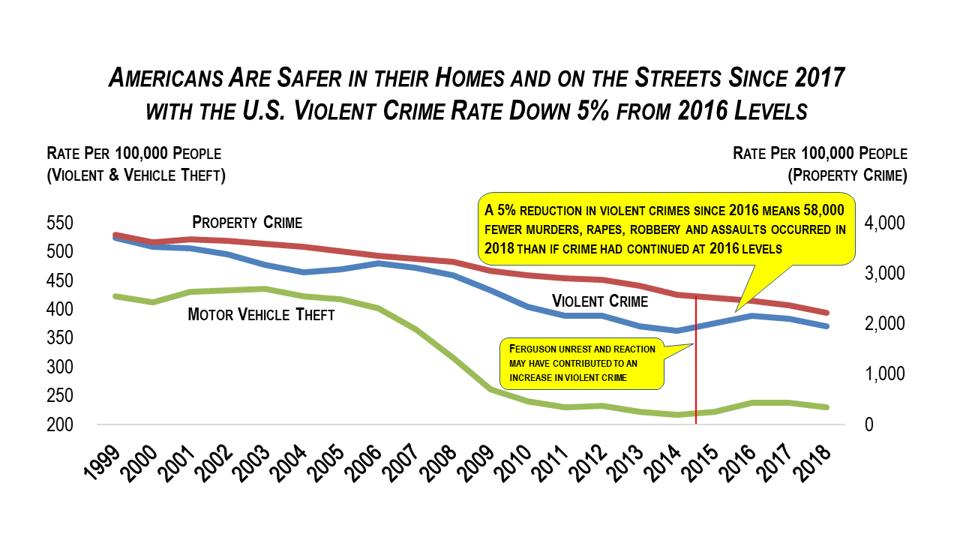

The FBI released its annual crime report a few days ago, showing the violent crime rate has dropped 4.6% since President Trump took office. Had the violent crime rate in 2018 remained at 2016 levels, almost 58,000 additional murders, rapes, robberies and aggravated assaults would have occurred.

The major property crime rate has also continued its steady national decline, with the rate of motor vehicle theft resuming its downward rate in 2018.

The U.S. violent crime rate is down 5% from 2016 levels after two years of increases in 2015 and 2016.

TEXAS PUBLIC POLICY FOUNDATION, DATA FROM THE FBI

The American criminal justice system—laws, policing, law enforcement operations, the judicial system, probation and parole officers, and our jails and prisons—play a part in public safety. But America’s crime rate is more than the sum of the effectiveness of our criminal justice system. The strength of our families and institutions, the role of faith, popular culture, welfare policies, and the availability of work and entrepreneurial opportunities all have an effect on what, in the end, is an individual responsibility: do we follow the law or not?

The “Ferguson Effect” is one theory as to why the nation’s violent crime rate saw an uptick from 2014 to 2016. In short, the “Ferguson Effect” hypothesizes that the widely covered shooting of a black teenage suspect by police in a St. Louis suburb in August 2014 led to widespread hesitation by police officers to do their jobs in some high crime neighborhoods. This may have contributed to a sense of impunity on the part of those inclined to commit crimes. Former FBI Director James Comey even suggested that police have become more reticent to enforce the law for fear of their actions being captured on video (the concern being that the video would go viral on social media, which would then lead to intense pressure to prosecute them for civil rights violations).

Though legitimate instances of police misconduct exist and should be independently investigated, there is also a danger in officers taking the path of least resistance when even well-founded stops are presumed to be instances of profiling or use of force in self-defense is presumed to be improper.

Research suggests the Ferguson effect likely was concentrated to certain urban areas and is one of many factors in crime rates. Undoubtedly, the media coverage of Ferguson and similar incidents, both those where police action was ultimately found to be justified or wrongful, drove a further wedge between police and communities.

Randy Petersen is a Senior Researcher in the area of policing at the Texas Public Policy Foundation (and a colleague of the author). His 21 years as police officer in Illinois and then directing one of the busiest police academies in Texas provides him with a perspective on what may be behind the crime rates.

“Policing is a uniquely local endeavor,” he observed recently.

“Police and sheriff’s deputies are integral parts of their communities,” he said. “Law enforcement is just a small part of what our nation’s police officers do, and it is the cold, hard part of it. Policing is about creating a community free of crime and preserving the quality of life, quite literally keeping the peace.”

Petersen went on to detail a major policy shift by the Trump Administration that has largely gone unnoticed.

“The past administration’s frequent resort to consent decrees, a coercive measure where the federal government oversees local policing operations, was reversed upon this administration’s taking office,” he explained. “When federal bureaucrats in Washington set standards for a police department under threat of sanctions, they set not only a floor but a ceiling. No police agency is going to innovate in its policing operations while under the watchful eye of an antagonistic Department of Justice—they will simply check the boxes and move along until the time runs out. The people closest to the community, who understand its needs, will instead defer all judgement calls to a distant and insensitive federal government.”

Petersen concluded by noting that, “To the extent that policing has affected the recent two-year drop in crime rates, it is no surprise that a president who has made clear his support for law enforcement, in words and deeds, would see the fruits of those policies in improved policing efforts and outcomes.”

Sustaining that crime rate drop requires more than just good policing backed up by a supportive president and public. It also requires being efficient and effective with the entire criminal justice system, starting with the premise that improved public safety is the goal.

Some 97% of people in prison will eventually be let out. Recidivism—when former inmates many fail and commit a new crime, harm a victim, and return to prison—has a significant effect on public safety and the viability of our communities. Research shows that there are proven steps that can reduce recidivism, making all of us safer while increasing the odds that our neighbors who commit crime are more likely to become productive citizens, rather than remain a threat and a burden on taxpayers.

The federal First Step Act, a bipartisan criminal justice reform bill signed into law by President Trump in December 2018, was inspired by successful criminal justice reform measures pioneered by lawmakers in Texas, Georgia and other conservative states. Specifically, the new law boosts efforts to prepare inmates for employment while in prison as well as post-release. The law also expanded alternatives to prison such as home confinement for low-risk offenders while implementing evidence-based treatment for opioid and heroin abusers.

While the federal prison system only holds about 10% of America’s inmates, reform at the federal level, if properly implemented and successful in its goal of improving rehabilitation and increasing public safety, may serve to encourage continued reforms at the state level.

The renewed drop in violent crime, and the continued decline in property crime suggest that President Trump’s actions and policies—combining support for law and order with public safety-focused criminal justice reform—is a winning combination for the American public.