President Trump signed the Tax Cut and Jobs Act into law on December 22, 2017. The tax cut, combined with billions in federal regulatory relief, reinvigorated the economic expansion which is now in its 126th month, making it the longest recovery in U.S. history.

While the tax reform law cut taxes for most individual taxpayers and corporations, one provision, capping state and local tax (SALT) deductions to $10,000 per filing household, benefits taxpayers living in low tax states more than in high tax states. Capping SALT deductions to $10,000 for filers who itemize their deductions has led to bitter criticism from elected officials in high tax states such as New York and California.

There are two prominent arguments in favor of the $10,000 SALT cap. First, the federal tax code shouldn’t encourage states and localities to levy high taxes, knowing a significant share of them would be subsidized by federal policy. And second, the vast majority of the approximately $80 billion a year in federal taxes raised due to the SALT cap would accrue to high-income households—meaning that if we lift the cap, high-earners would benefit the most.

The U.S. House passed H.R. 5377 on Thursday to repeal portions of the 2017 tax cut, including the SALT cap. The 218 to 206 vote brought out some interesting partisan and regional divisions. There were 16 Democrats who voted against the bill, including progressive New York Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Her “no” vote reflected the view of a tax policy staffer with the big labor-backed Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), a progressive think tank who noted that the SALT cap repeal “…mostly benefits rich people.” Only five Republicans voted for the bill, three from New York, and one each from New Jersey and Pennsylvania—all states featuring high state and local taxes.

The House’s SALT repeal bill faces no chance of passage in the U.S. Senate. At the same time, a federal lawsuit against the tax cut brought by New York and other high tax states, was thrown out by a federal judge in late September.

So, with the Trump tax cut safe for the foreseeable future, how are the states faring on the jobs front?

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its state-level jobs report today for the Month of November, providing 23 months of employment information to track how the Tax Cut and Jobs Act may have shaped job growth trends across America. The results strongly suggest that the 27 low tax states (with average SALT deductions below $10,000 in 2016) are significantly outperforming the 23 high tax states and the District of Columbia (where filers claimed more than $10,000 in SALT deductions).

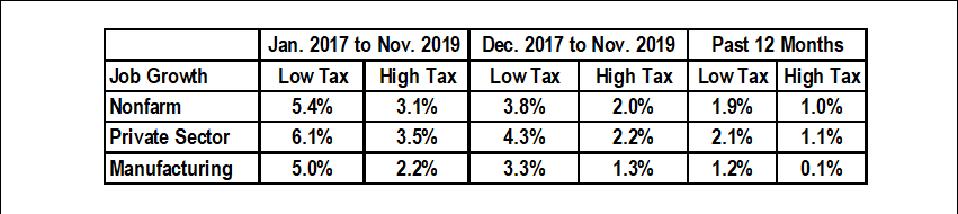

From December 2017 to November 2019, the low tax states added nonfarm payrolls at a rate 93.8% greater than the high tax states. Nonfarm jobs include those in the government sector. Limiting the scope of job growth to the private sector, where small business owners’ decisions on when and where to grow their businesses are directed affected by the tax code, shows and even larger job creation advantage for the low tax states, with a 97.9% higher rate of job growth in the past 23 months. Capital-intensive manufacturing shows an even larger disparity, with the rate of manufacturing jobs growing 3.3% in the low tax states compared to 1.3% in the high tax states, a massive 151% disparity in favor of the low tax states. In the past 12 months, the difference in manufacturing job growth is an astounding 1,209% advantage in favor of the low tax states. This may be because manufacturing facilities take longer to get up and running than do other sectors such as retail, with the effect of the tax cut being slower to manifest in this sector.

The table below shows the percentage of jobs added in three categories, nonfarm, private sector, and manufacturing over three time periods, since President Trump was sworn in in January 2017, since the passage of the tax cut in December 2017, and over the past 12 months.

Job growth in the 27 low tax states has been substantially higher than in the high tax states since … [+]

TEXAS PUBLIC POLICY FOUNDATION COMPILED WITH DATA FROM THE U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 profoundly affected the economy, extending and strengthening the expansion, and reordering incentives to invest at the state level. Until politicians in high tax states decide to cut taxes, they are likely to continue to see weaker relative job growth than in their low tax peers such as Texas and Florida.