There’s no end to fun surveys that purport to measure patriotism among the states, with military enlistments often part of the criteria.

However, using enlistment rates to gauge the regional willingness to volunteer for the armed forces betrays a common misunderstanding of the way the U.S. military operates. What matters is accessions to the military, not enlistments. Accession is a term used when a civilian joins the military, having passed mental, physical, educational and legal standards, and swears an oath to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Enlisted personnel—in other words, not commissioned officers—enlist for a term. When that term is up, they can leave the military or choose to reenlist. Thus, states with a large active duty presence will also then see many enlistments.

Propensity to join the military became vitally important to national security with the last group of men conscripted in December 1972. The move to an all-volunteer force was tremendously controversial, with military leaders fearful that they would be unable to maintain force levels required to deter the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

But research showed that advertising and benefits in the form of educational incentives could attract enough talent. And, once launched, the advantages of a professional all-volunteer force quickly outweighed the disadvantages, with higher reenlistment rates, better quality recruits, and more people deciding to make a career out of the military.

Today, contrary to popular myth, members of the U.S. Armed Forces are mostly drawn from the middle class, with the lowest income quintile being slightly underrepresented, and the highest quartile being even less represented, with about 17% of enlisted personnel coming from the top 20% of neighborhoods by income. Further, 92% of accessions to active duty have a high school diploma, compared to 90% of adults age 25 and older.

But as representative of the nation as our armed forces are, there are stark regional differences in the makeup of our military, with the South contributing more than its fair share of personnel and the Northeast largely lagging behind, with a few exceptions.

Reviewing a 2016 report from the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness titled “The Population Representation in the Military Services” shows that California (17,729), Texas (16,139) and Florida (11,552) had the largest number of people enlist in the military. But these three states are the three most-populous states. Further, new recruits are mostly 18-to-24 years old with about 0.5% of them volunteering and being accepted for active duty each year.

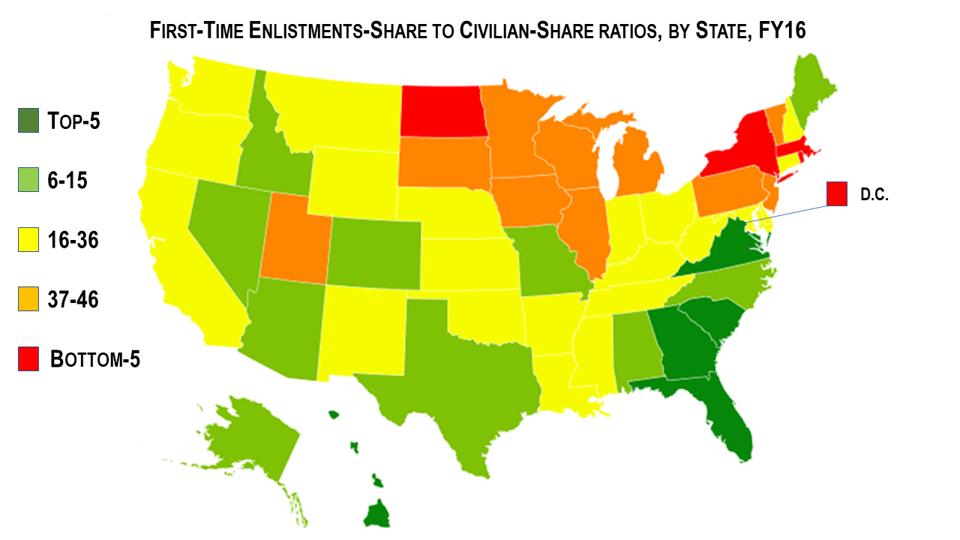

Looking at each state’s share of recruits by the number of 18-to-24-year-olds in the state determines how well or how poorly a state is doing compared to its recruitable population. By that measure, the top five states in 2016 were: Hawaii, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia and Florida. The five places with the smallest share of recruits were: Washington D.C., North Dakota, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New York.

It’s somewhat curious to see North Dakota on the laggards list—until you understand that there is a close statistical link to recruiting and unemployment rates. In 2016, the official unemployment rate averaged 3.1% in North Dakota, as that state’s oil fracking boom was in full swing, giving the state America’s fourth-lowest unemployment rate, tied with Nebraska and just behind South Dakota, Hawaii and New Hampshire. The national unemployment rate averaged 4.9% in 2016.

Looking at accessions as a share of the prime recruiting age population shows some regional concentrations in the Southeast Atlantic and Hawaii.

As a share of the population, ages 18-to-24, there’s a strong tradition of service in the Atlantic … [+]

TEXAS PUBLIC POLICY FOUNDATION WITH DATA FROM THE DOD

Hawaii is especially interesting as that state had America’s second-lowest unemployment rate that year, meaning the armed forces had heavy economic competition.

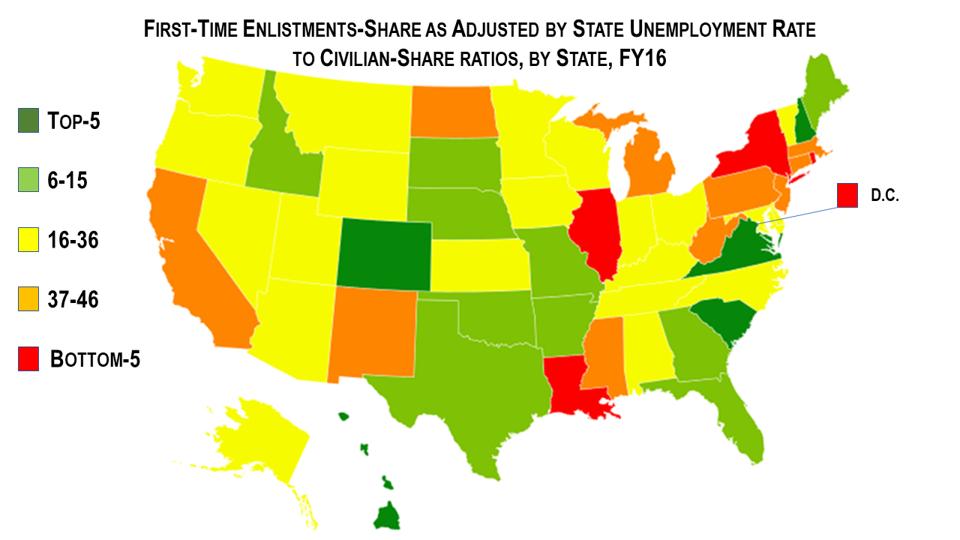

Factoring for unemployment in the states slightly changes the map with North Dakota and Massachusetts being replaced in the bottom five by Louisiana and Illinois. In the top five, Colorado and New Hampshire displace Florida and Georgia.

Culture and tradition play a role in the decision to join the military, but so too does familiarity with uniformed service. As military service becomes rarer with the passing of the Greatest Generation of WWII veterans, as well as the millions who were drafted during the Cold War and Vietnam-era, military service is increasingly concentrated in families and in communities which host large military bases.

Looking at the likelihood of joining the military after accounting for economic conditions shows three factors are somewhat predictive in the whether a state’s younger generation is inclined to join: the percentage of all-volunteer-era veterans in a state (1975 and later), the share of active duty personnel in a state and, not surprisingly, the share of the state’s population with a hunting license, with higher percentages of each being positively correlated to a higher enlistment rate. Other factors checked but with little statistical connection to military service included how urbanized a state is, its political leanings, its Supplemental Poverty rate, and its income inequality (Gini Coefficient).

After accounting for the unemployment rate at the state level, the five states with the largest … [+]

TEXAS PUBLIC POLICY FOUNDATION WITH DATA FROM THE DOD AND U.S. BLS.

As America appears on the verge of a renewed superpower confrontation, this time with the People’s Republic of China, it would behoove policymakers to examine how best to recruit and maintain an all-volunteer force that continues to reflect our nation demographically while also seeking to address regional imbalances.