In a few short weeks, a virus with origins in China has brought the American economy to a near-halt. Public health officials, 16.5 million health-care workers, and tens of thousands of scientists are working overtime to reduce the fatalities, heal the sick, and find a cure.

Congress reacted as only it knows how—by spending more than $2 trillion on programs, payments, and loans, allocating about twice as much in days as what it took to fight World War II in 1944, the peak year of our war effort.

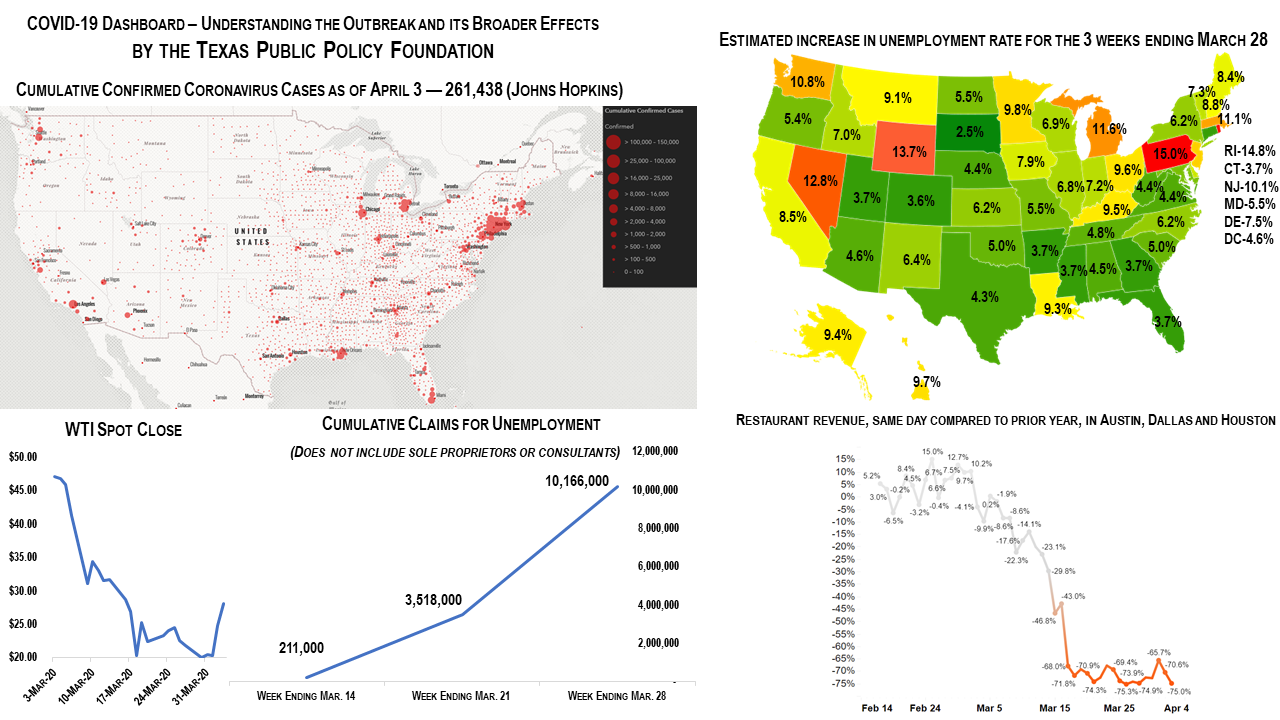

Public health experts, relying partially on models dependent on thoroughly untrustworthy “data” from the People’s Republic of China, have pushed for social distancing measures that have resulted in governors and local officials shutting down vast swaths of the economy. Economists say unemployment will quickly rise to as much as 15 percent from the former level of 3.5 percent, with the economy shrinking by 10 percent in the first quarter followed by another 25 percent loss in the second quarter before rebounding.

Here’s what this looks like on a practical level. Prior to the virus, America’s restaurants were having a great year, with same day revenue running about 5 percent ahead of last year. Then came the Wuhan Flu.

Restaurants across the nation went from about 15 percent of their revenue coming from takeout orders to 70 percent, while revenue plummeted about 80 percent from last year. Some 5.5 million people worked serving food and beverages. Not now. And a large number of eateries will not survive.

As of April 3, 49 percent of America’s 261,438 COVID-19 cases are in New York and New Jersey, clustered in areas featuring the highest population density in the United States. Although the virus is relentlessly spreading in every state, social distancing is easier to practice on the prairies and plains of Texas than on the subways of New York City.

Testing is becoming quicker, easier, and more accurate, with more than 1 million conducted to date in the United States. Critical ventilator production is ramping up rapidly. And treatments are becoming more widely known and available, including hydroxychloroquine and blood plasma from people recovering from a COVID-19 infection. In about a year we may have an effective vaccine.

But what if another virus emerges out of China? A Chinese biolaboratory has been shown to have been tinkering with bat viruses, and selling used up lab animals to local “wet markets” for a little extra side income. Is America prepared to spend another $2 trillion—assuming it can borrow that much again?

Every few years the nation’s civil engineers produce a slick “Infrastructure Report Card.” In 2017, the report card gave America a “D+” and recommended spending an additional $1.5 trillion over a decade on top of the $1.8 trillion already committed on roads, bridges, airports, water systems and other infrastructure. If we didn’t, the engineers warned of more road deaths, failing dams, and a cost to families of about $3,400 annually in lost productivity.

But America isn’t an engineer-ocracy, as a result, the nation’s infrastructure grade will probably always be below average. Neither is America a doctor-ocracy, even though during this time we are giving our medical professionals more attention and resources than usual, as we’re afraid of a new and deadly virus.

All goods and services compete for limited resources. Health and safety, social welfare, housing, transportation, entertainment, and even national defense are balanced in a system of tradeoffs that, for the most part, seeks to create supply to meet demand.

Our nation’s 16.5 million people working to provide health services make up the largest sector of employment in the nation, having surpassed manufacturing employment in 2003 and retail employment in 2017. Many of them support America’s aging population, and the fight against the virus will boost these numbers even higher.

Imagine for a moment that the nation were ruled by dictatorship of doctors. Private ownership of guns would be curtailed. All tobacco products would be outlawed. Sugary drinks would be heavily taxed. Taxes on alcohol would go even higher. Football, boxing and other dangerous sports would be banned.

Vaccinations against common diseases would be mandatory. Mentally ill people on the street would be institutionalized. And, in the fight against infectious diseases, South Korea—or even the People’s Republic of China—would be seen as a model worth emulating. Because resources are finite, there would be less spending on roads and defense and even entertainment.

In the end, we might not live longer, but it would feel like it.

In South Korea (a democracy, we should note), government officials used surveillance cameras, credit card transactions, and cellphone GPS data to map the social connections of suspected COVID-19 cases and then force quarantine. In China, entire apartment blocks where the virus was running rampant were said to be have been welded shut at night.

Americans should chaff at such intrusions. It’s why we struggle over questions like involuntary commitment for the mentally ill on the streets, gun control, and risky activities. Now we chaff at being told when we can return to work or go to a restaurant.

We’re a free people, able to make choices—even ill-informed ones—about our own lives and wellbeing. It’s called liberty. It’s not easily measured, but we value it and have since before Patrick Henry proclaimed it to the Virginia Convention 1775 when he said, “Give me liberty, or give me death!”

While President Trump has declared that we are at war with an invisible enemy from China, our sophisticated health-care system, equipped by an arsenal of innovation made possible by free markets and prosperity, may allow us to enjoy both liberty and health.