Texas is in the news, and not in a good way, over an increase in COVID-19 cases over the past four weeks. There’s quite a bit of speculation over why the virus, which largely bypassed the Lone Star State until the end of May, suddenly seemed to become more pernicious.

Some point to a lack of enforcement for social distancing measures and masks. Yet California, a state of similar size and demographics, where Democrat Gov. Gavin Newsom was far more aggressive in pursuing a shutdown than Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, has seen a case increase of about the same magnitude, which even started at about the same time as Texas.

Unemployment numbers can give us a sense of how widespread the shutdowns in each state were. Since February, California’s unemployment rate jumped 12.4 percent to 16.3 percent in May, while Texas’ saw an increase of 9.5 percent to 13 percent over the same period.

Prior studies have suggested a weak connection between the intrusive government measures to slow the spread of COVID-19 and the progression of the virus, suggesting that due to its ease of transmission in certain environments, such as mass transit and residences, it will inevitably spread until a certain percentage of the population develops immunity.

Had California’s unemployment rate gone up only as much as the rate in Texas, the state would have saved about 600,000 jobs. What did California gain for this sacrifice? Perhaps not much. According to The New York Times’ interactive coronavirus site, as of June 25, California’s per capita case count is 9 percent higher than Texas’s and its per capita fatality rate is 89 percent higher than in Texas.

How to Understand Statistics

Of course, both states pale in comparison to the losses in New York, where Democrat Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s deadly misstep of placing seniors with active cases of the virus into nursing homes to clear space in hospitals resulted in tens of thousands of additional deaths. New York’s per capita case count remains about four times higher than that in either California or Texas, and its fatality rate is 11 times greater than California’s and a staggering 21 times greater than Texas. While the trends are troubling in America’s two most-populous states, due to several factors, they aren’t likely to get close to, much less exceed, New York’s debacle.

The intense focus by the media and the political left on largely conservative states where the virus toll is mounting (from a low base) plays into the very human, and often irrational, perception of risk. If the number of cases goes from 10 to 20, that’s a doubling, and the public gasps. Yet if the number of cases goes from 1,000 to 1,100, we collectively yawn.

Similarly, we don’t do well with unseen but very real effects, as observed by French economist Frédéric Bastiat in 1850. To list one example, COVID-19 largely spares school-age children its most harmful effects, meaning measures like canceling school and disrupting friendships may lead to far greater losses from suicide than the virus could ever threaten. Further, the lost months and years of education will visit negative consequences on the COVID generation for the remainder of their lives. But those consequences are unseen—for now.

These Explanations Don’t Hold Water

Returning to Texas, there are four reasons frequently given for the recent increase in cases: Abbott and those liberty-loving Texans opened up too soon (that California surged while locked down more than Texas doesn’t help this argument); cases appeared to mount just after Memorial Day, when many people visited friends and relatives; cases increased among the young after large protests that started about a week after Memorial Day, and; large numbers of infected Mexicans and Central Americans are fleeing across the southern border as Mexico has forgone any coherent COVID response, leaving its already weak medical system wholly unprepared to cope.

Regardless of the reasons for the virus’ increased prevalence in Texas—something likely unavoidable until enough people develop immunity, whether through catching it or by being vaccinated once a vaccine is developed and proven—the state is now dealing with an increase in hospitalizations. This means we’re hearing calls for Abbott to roll back the state’s economic and social opening.

Unfortunately, the rhetoric over Texas’ hospital capacity is clouded by a lack of understanding and, in all too many cases, a ghoulish partisan glee.

Texas Is Ready If the Increase Continues

The first thing to understand about hospitals is that they are businesses and if they don’t generate more income than expenses, they are forced to lay off doctors and nurses, forego the acquisition of costly but life-saving medical equipment, and eventually close their doors. This was seen all over America a few months ago when hospitals were directed to cut back on “elective” procedures to make way for an expected wave of coronavirus patients that, with the exception of some states in the Northeast, thankfully never materialized. This led to a round of layoffs as hospitals nationwide struggled with a plunge in revenue.

The second factor to consider is that Abbott’s COVID-19 response team, lead by former state representative and anesthesiologist Dr. John Zerwas, put together a flexible five-phase system to expand hospital bed, ICU bed, and ventilator capacity as needed. This advance work led to an 89 percent increase in available capacity from the onset of the virus to mid-June.

Lastly, as Texas’ regional hospital systems and public health officials saw the immediate threat from the virus recede in May, the number of critical “elective” procedures rose, as people with heart disease, breast cancer, colon cancer, and other life-threatening conditions, sought treatment—in too many cases, dangerously delayed.

Texas Hospitals Have Ample Room to Handle a Surge

Thus, uninformed critics of Texas—or outright partisan scaremongers—claimed in recent days that Houston’s medical system was about to be overrun by virus patients, pointing to the slender margins of the region’s ICU capacity, with 95 percent of the beds full. The critics failed to note two rather important factors.

As an example, at the Texas Medical Center, one of Houston’s largest hospital networks, some 70 percent of the available ICU beds as of June 23 were taken by non-COVID patients, with 27 percent treating patients suffering from the virus and 3 percent of the beds available. However, that total ICU number was without activating the system’s “sustainable surge” capacity, which would quickly add another 373 beds—more than the 362 beds currently being used by virus patients.

Further, as virus cases are admitted to the hospital system, “elective” patients can be cycled out as they recover and elective procedures can be scaled back to make more room. If the Texas Medical Center receives even more COVID patients, they can activate their “unsustainable surge” capacity, adding another 504 beds for a total of 2,207 beds in a system currently treating 362 COVID patients—a six-fold increase in ICU capacity currently treating virus patients. The misinformation got so bad that the leaders of Houston’s hospital network issued a statement on Thursday assuring Houstonians that they had ample capacity to handle the expected increases in COVID-19 patients.

Our Ability to Treat Wuhan Flu Patients Has Increased

The focus on hospitalizations and more serious ICU or ventilator use misses a few other vital factors. First, our understanding of the virus and how to treat it has improved significantly over the past few months.

We know to lay patients prone if they are having breathing difficulty, avoiding use of ventilators as much as possible. We now have a wider array of treatments that appear to improve the chances for recovery. And, due to increased testing, a larger share of people who were previously not likely to be hospitalized are now being placed under observation.

Further, the number of patients receiving treatment might be higher for the simple reason that hospitals have been incentivized to take them due to the 20 percent financial incentive passed by Congress for treating Medicare patients with COVID-19, with many insurance companies joining in after being pressured by governors.

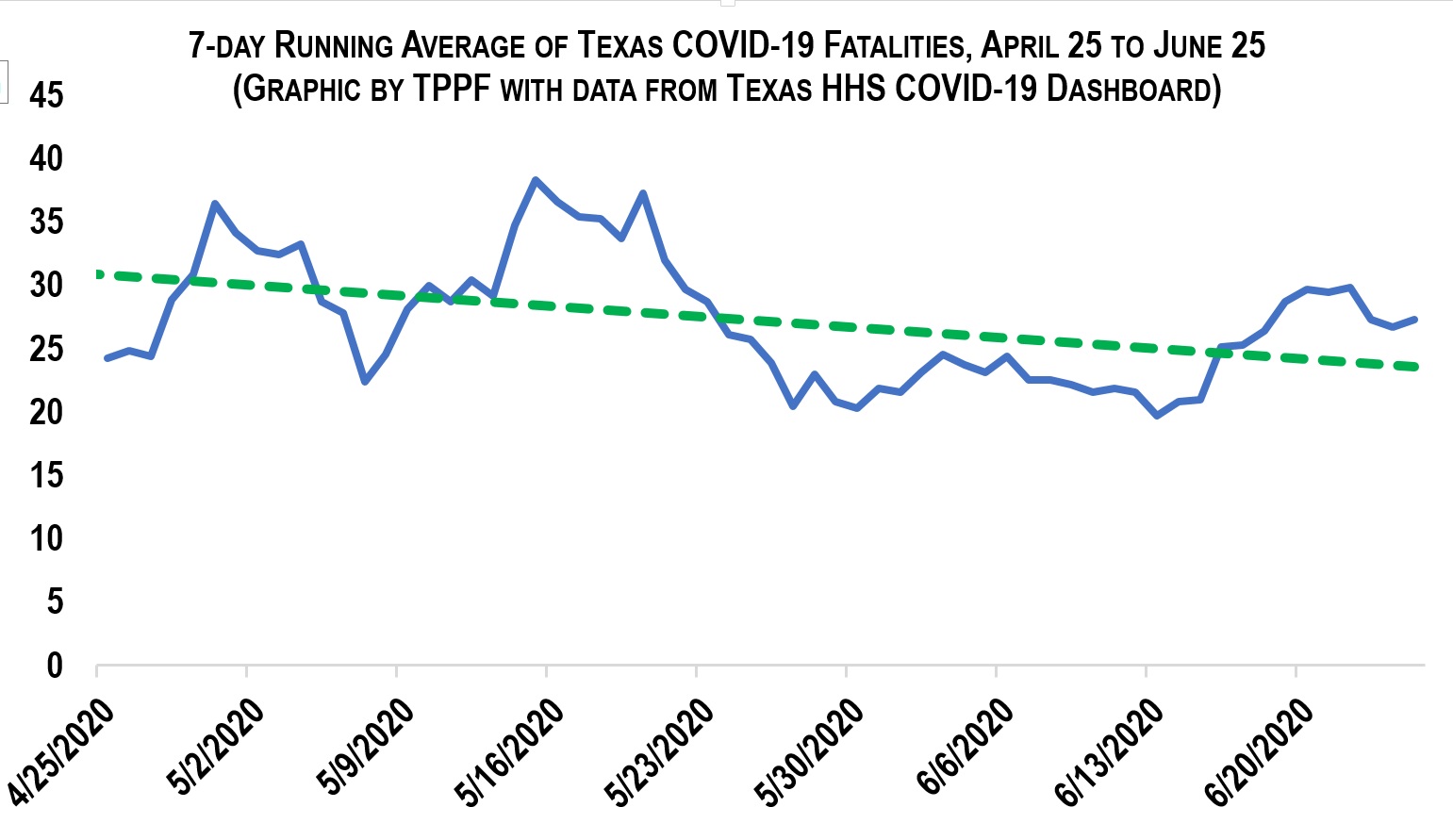

This leads to one statistic that, in its finality, is the true arbiter of how hard a state is being hit by COVID-19: fatalities. In this grim statistic, Texas is still doing relatively well, although time will tell, as deaths typically lag cases and hospitalizations by six to nine days.

Even so, the running seven-day average of deaths in Texas has been trending down since it first peaked in late April. In New York City, 584 people lost their lives to the virus on April 7. New York City has 28 percent of Texas population. Texas’s worst day of fatalities was 58 on May 14—less than one-tenth New York’s grim toll with more than three times the population.

Looking at New York state, with 65 percent of Texas’ population, Texas would have to suffer 47,700 fatalities to reach the Empire State’s per capita death toll. As of June 25, Texas had lost 2, 296 of its residents to COVID-19.

Is the virus spreading in Texas? Yes. Is it time for panic? No.