We needed some groceries. Caring for my 95-year-old father-in-law at home, complicated by COVID-19 concerns, led us to do what we have increasingly done over the past few months: we ordered online for at-home delivery. At the appointed time, Billy, the driver, showed up with the groceries, driving his own car.

From a respectful distance, I asked Billy what he did for a living before the pandemic. He said he used to drive Uber in Houston, Texas. With the arrival of COVID-19, however, the number of people needing a ride dropped. He started delivering groceries to earn a living, but the business in Houston started to get sparse. Then, through his motorcycle club, Billy heard the greater Austin area had stronger demand.

So, for the past two weeks, he’s been delivering groceries Monday through Friday, living out of his car, grabbing showers at a truck stop, then heading home for the weekends.

In California, Billy likely wouldn’t have a job because Assembly Bill 5, passed late last year, would classify Billy as an employee rather than an independent contractor. So, instead of getting paid via an app like Lyft in cooperation with the grocery store chain, the grocery chain would be required to hire Billy.

As a result, Billy would be paid the minimum wage, would pay workers comp and unemployment taxes, and receive paid sick and family leave and health insurance. Of course, as a traditional employer, the grocery store would likely demand certain hours and other standards from Billy. Billy didn’t seem to be a man who would enjoy such regimentation.

In California, Big Labor Still Calls the Shots

As with much of what passes into law in California of late, AB 5 is a labor union bill. Its unstated intent is simple: force the millions of Californians in the gig economy to unionize, providing hundreds of millions of dollars in dues money that unions can use to further consolidate control over the state, and still have millions left over to establish strongholds in other states like Texas.

As with any intense battle, there is collateral damage. While AB 5’s main target is the burgeoning app-based gig economy — Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart, and Postmates — the law also covered freelance writers while excluding another 50 professions, including attorneys and real estate agents. One of the more immediate ironies of freelancers no longer being able to ply their trade in California — writers, cartoonists, or photographers who exceed 35 paid submissions per year to the same company must be converted to employees — were the mass layoffs over at Vox last December.

Vox writers had been enthusiastically backing the new law, likely thinking it “stuck it to the Man.” Then Vox Media, based in New York, terminated hundreds of freelance writers and editors in California two weeks before the law was due to go into effect on Jan. 1. In place of the 200 freelancers who covered sports for SB Nation, including out-of-state writers who covered teams based in California, Vox planned to set up a group of 20 full and part-time staffers. Due to Vox Media’s earlier unionization, these new employees will likely be members of the Writers Guild of America, East.

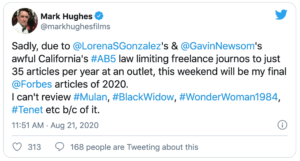

So, rather than 200 people able to set their own schedules and largely determine their own compensation from a variety of sources (something especially valuable in the uncertain time of COVID-19), there are now 20 unionized employees. Other writers were harmed as well. Over at Forbes, film critic Mark Hughes hung up his keyboard in an August 21 tweet:

The Growing Alliance Against Proposition 22

With billions in revenue at stake in the nation’s largest state — as well as the likelihood of copycat legislation rippling out first into the farther left states — Uber, Lyft, and Doordash each contributed $30 million to overturn AB 5 via a ballot initiative this November. They were later joined for $10 million each by Instacart and Postmates, for more than $110 million in support of Proposition 22 so far.

By California standards, this is a larger-than-average effort. When the opposition starts to engage and the app-industry responds, the campaign will escalate quickly.

By comparison, in 2008, California’s major American Indian casino interests sought to expand the number of casinos they could operate via four separate initiatives. Las Vegas opposed the effort. The two sides spent $172 million to fight it out. The American Indians won.

In the last election cycle in 2018, one of the more hard-fought California propositions would have allowed local rent control. Prop. 10 failed, but not before about $86 million was spent for and against it.

Now, the app lobby has attracted a broad range of allies for the fight, including the California Peace Officers Association, California Police Chiefs Association, and the California State Sheriffs Association, (who likely approve of the idea of fewer drunk drivers on the road), as well as the California NAACP State Conference, the California Chamber of Commerce, the CalAsian Chamber of Commerce, and the National Black Chamber of Commerce. In most normal states, this and $150 million would be sufficient for victory. California isn’t a normal state.

All the Usual Suspects

Arrayed in opposition to Prop. 22 is the California Teachers Association — the state’s most powerful union — the California Labor Federation (AFL-CIO), the California State Council of Laborers, the SEIU, California State Council, State Building and Construction Trades Council of California, and Unite HERE. Joe Biden and his running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris, are also opposed — showing that in a choice between the NAACP and Silicon Valley versus Big Labor, Democrats will always choose the latter.

Unfortunately for the app lobby, its access to endless piles of cash combined with being locked in an elite San Francisco Bay Area cultural bubble will likely spell the effort’s doom at the ballot box. This was previewed in Austin, Texas in 2015 and played out over a year as the city’s increasingly progressive city council voted to outlaw Uber and Lyft’s business model at the urging of the local taxi companies.

The rideshare app companies countered with what became Austin’s most costly ballot measure, spending $8.6 million in a city of 940,000 to overturn the council’s ordinance in May 2016. Texas voters responded poorly to the Californian onslaught and rejected the measure by 12 points, in spite (or because) of it, spending more than seven times as much as Austin’s previously most-expensive campaign.

Uber and Lyft immediately left town in response, calling Austin’s bluff. For a time, Austin made do with locally crafted apps that complied with the City Council’s regulations (along with illegal workarounds). But eight months later, the new Texas legislative session convened in Austin and the rideshare firms bought in Texas’ best lobbyists, spending a few million dollars to do what almost $9 million couldn’t in Austin: change the law by preempting local rideshare restrictions.

Lawmakers answered, agreeing with Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) that a “patchwork quilt of compliance complexities are forcing businesses out of the Lone Star State,” citing not only Austin’s actions but similar moves against Uber and Lyft in Houston and San Antonio. The new Texas law did apply some regulation to the rideshare apps, but it was uniform and still allowed them to operate. Uber and Lyft’s lobbying effort managed to pass state preemption laws in all but a handful of states in the aftermath.

Worth The Fight

Back in California, a state appeals court granted a stay of AB 5 for the rideshare firms on Aug. 20, pending the results of the November ballot initiative. Polling earlier in the month showed voters inclined to support Prop. 22 by a margin of 41 percent to 26 percent. But the rule of thumb in California propositions is that you want to be comfortably above 50 percent approval if there is organized opposition.

If Uber, Lyft, and other app firms spend as much in California on a per-capita basis as they did in Austin, they’d deploy a staggering sum of $365 million to pass the initiative (with $35 million or more spent in opposition). For the app firms, it would be worth it. If California turns against their business model, their only recourse would be to seek relief at the federal level — where labor unions’ hold on the national Democrats is just as strong as it is in California.

Unfortunately, the app firms missed a huge chance to expand their coalition by excluding hundreds of thousands of freelancers and other independent contractors from their initiative. A simple referendum to overturn AB 5 in its entirety would have done this.

If Prop. 22 does go down in flames, look for an acceleration of driverless car technology to displace human-piloted taxis and rideshares — and look for California’s union-controlled Luddite lawmakers to outlaw those as well.