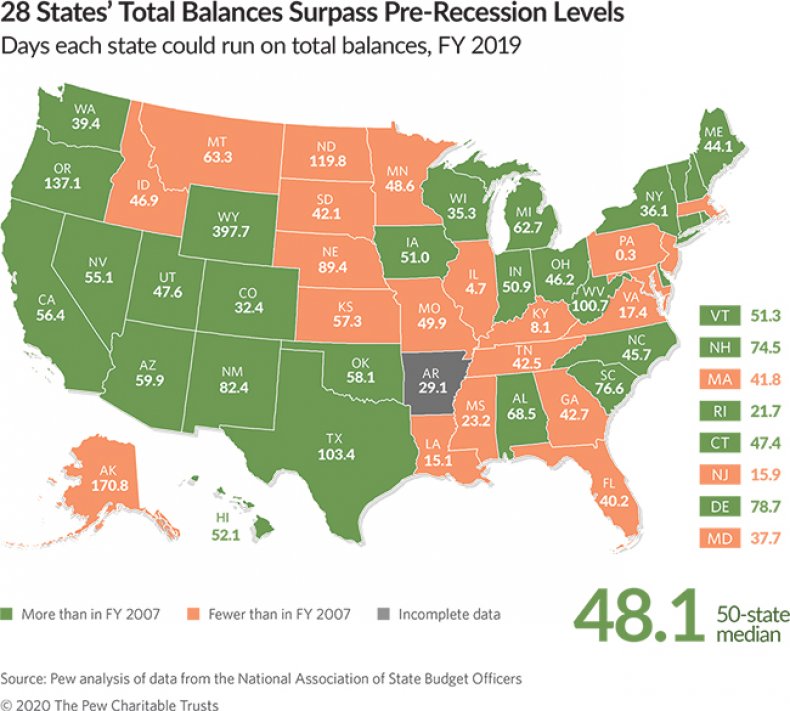

In what seems like a lifetime ago, state government finances across the nation were moving in divergent directions, with 28 states having replenished their fund balances above what they held before the onset of the recession in 2007. Meanwhile, states such as Pennsylvania and Illinois were dangerously low on fiscal reserves, with each state having less than a week of cash on hand.

But then came the coronavirus.

A graphic below from a March 18, 2020 Pew Charitable Trusts report entitled “States’ Financial Reserves Hit Record Highs” shows the vast range in fiscal health among the states, with the average a state could operate without revenue being 48.1 days.

Compounding some states’ weak financial position is their unfunded government worker pension obligations. In the case of Illinois, its 4.7 days’ fund balance is even more tenuous when considering its large government pension system obligations. According to the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy’s Pension Tracker, in 2017, the market value of Illinois per household government pension debt was $76,398, the fourth-highest in the nation after Alaska, California and Connecticut.

Even in California, where leaders have touted the state’s fiscal surpluses, the underlying financial picture isn’t as rosy. Because California politicians have promised so much in the way of deferred compensation to government employees in return for government labor union support at election time, California’s pension spending has doubled over the past decade to support the growing fiscal requirements of meeting defined-contribution plan obligations. When factoring in California’s pension shortfall of up to $1 trillion, the $7 billion budget surplus it expected before the virus hit doesn’t appear so robust.

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its death and suffering compounded by the continuous stream of lies and deception emanating from the People’s Republic of China, has greatly weakened the global economy.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 37 percent of its value in less than six weeks, before trimming its losses to 19 percent of February’s record high. This decline in market value will eventually hit state pension funds, since any reduction in assets must be made up through larger contributions from government employees and state and local governments. This forces states to levy higher taxes or cut spending to fulfill their legal promises to pensioners, which cannot, at present, be renegotiated as states cannot legally declare bankruptcy.

The wider economic fallout from the virus and governments’ response to it has been unprecedented.

Congress appropriated more than $2 trillion in response to the virus. In inflation-adjusted terms, this sum is about double what America spent to fight World War II in 1944, the height of our war effort.

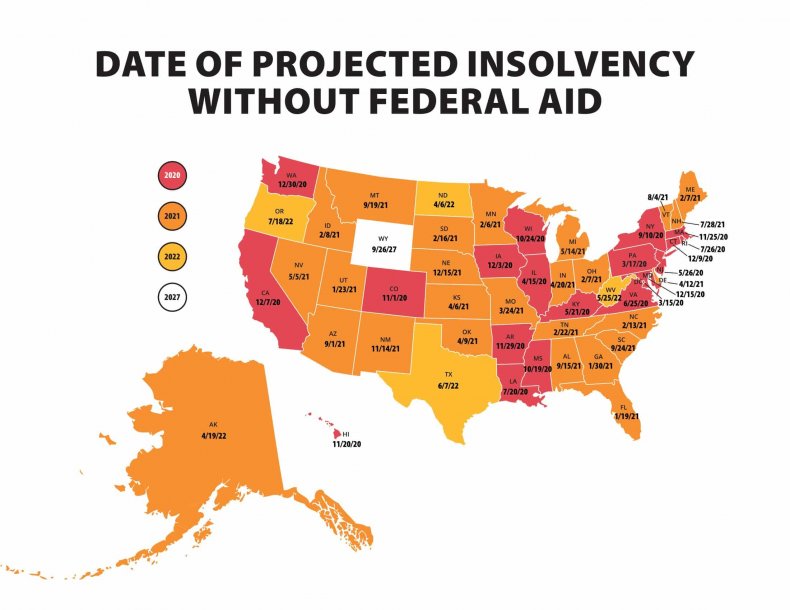

In addition to assistance to individuals and businesses, the money for states and local government falls into two main categories. The first are funds designated for the increased public health system response. The second is some $272 billion available in grants to make up for lost state revenue. In fiscal year 2019, states spent $2.1 trillion, so the federal government has allocated about 13 percent of state expenditures to help ensure states won’t become insolvent in the near term.

Depending on the mix of state revenue sources—property taxes being the most stable, followed by sales taxes, income taxes, corporate taxes, and excise taxes on oil and gas—states will see a wide range of fiscal stresses on top of what is expected to be more than 20 million newly unemployed American workers.

Without that incoming $272 billion in federal aid, 19 states would have faced insolvency this year—with Pennsylvania and Illinois already in a position to resort to short-term borrowing due to lack of cash on hand. At the other end of the ledger, Wyoming, a state heavily dependent on tax revenues from energy sales, has socked away such a large rainy day fund that it could likely operate without significant budget cuts or tax increases until 2027.

But ready availability of almost limitless federal funds for the states and local governments has led to what might be an unintended consequence—an increased reluctance on the part of elected officials at the state and local level to agree to get the economy moving again.

With what appears to be the potential to have their entire pandemic-induced tax revenue shortfall covered by the federal government, a major point of pressure has been lifted off their shoulders. Unlike during the Great Recession 12 years ago, state and local governments don’t yet face pressure to reduce spending or increase taxes. As a result, at least from a fiscal standpoint, there is little incentive for governors to agree to let people get back to work—even while at the federal level, debt is piling up at rates not seen since the nation fought World War II.