Henry Ford once said “a customer can have a car painted any color—so long as it’s black.” The automobile was new to the market, and Ford wanted his factories to run so efficiently that the cost could be low enough “that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one.”

Once competitors entered the market, that approach obviously changed. New automakers offered different colors and more choice on a variety of options. And because of competition—and relatively little government intervention—one thing has remained remarkably consistent: the cost of an automobile (adjusted for inflation).

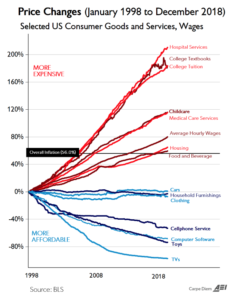

Graph of price inflation in the medical industry compared to other markets. Source: Bureau of Labor and Statistics.

Unlike the free-market environment that exists for the manufacture and sale of automobiles, health care operates in a heavily regulated market. A further complication of the healthcare industry in the United States is that it is tied to employment—which is something that sets us apart from people in other countries.

Employer-based health insurance was not common before World War II. On October 3, 1942, President Roosevelt via Executive Order froze any and all wage increases in both the private and public sector. The wage freeze, however, did not apply to employer-provided insurance and pension benefits. So employers—fiercely competing for workers—were left with no other options but to offer more competitive benefits packages, including health insurance. By 1953, 63% of Americans had employer-based health insurance, compared to only 9% in 1940.

But this phenomenon of employer-based health insurance, unique to the U.S., threatened individuals with the risk of losing health insurance when they changed or lost their jobs. In other words, the federal government itself created the problem of pre-existing conditions by tying health coverage to employment.

Still, some solutions have been introduced, in an effort to address portability. One of the most substantive has yet to be implemented. In January 2020 the Health Reimbursement Agreement (HRA) created under Executive Order 13813 will allow employees to shop, compare, and purchase their own health care plans that best fit their needs and goals, and most importantly, be reimbursed by their employer. In this new paradigm, the employer may offer a set amount across nine classes of employees (based on hours worked, location, and more) to reimburse employees for the purchase of their own health care policies, and for certain out-of-pocket medical expenses.

Large companies—and the 30% of employers with less than 24 staff members—currently offer health plan options to their employees. However, those options are usually limited to just a few variations of the same product. Empowering employees to shop for their own plans permits the companies to leave the insurance risk industry, and to do so with fixed costs and budget. The company does not own the health care plan, the individual does. And it’s highly portable, should that employee move to another employer. This transfer of time, resources, and risk will be invaluable for American companies, allowing them to focus on their product or service—their actual business.

The Treasury Department expects 800,000 employers to opt for providing HRAs to over 10 million employees, adding to the 17 million Americans currently purchasing individual health care coverage. The number of HRA participants will likely increase over the long term as competition for this giant new pool of insureds drives market efficiencies, while the advantages to both employers and employees continues to draw new interest.

Making informed choices on which services to receive, and from which providers, will further empower the American health care consumer. This new layer of competition will be a trigger for the free market forces to take effect by creating a class of educated consumers determining and choosing their best value.

The American business community is grateful for the shift of applying basic and rudimentary free market principles to the overly inflated and opaque healthcare industry. We can now allow America’s widget makers to focus on their widgets, and not insurance risk.