After planned blackouts to reduce wildfire risk left almost 2 million people without power in Northern California, politicians and bureaucrats scrambled to lay blame.

Blackouts have a powerfully toxic political legacy in California. In 2000 and 2001, a series of blackouts and price hikes amidst a botched partial deregulation of the electricity market was a major contributing factor in the recall of Democratic Gov. Gray Davis in 2003.

Marybel Batjer, President of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), is now the point person for California’s dominant political establishment as it struggles to ensure that the public blames the electric utilities for the blackouts, rather than the politicians whose policies caused the current fiasco.

Batjer knows firsthand the political potency of the blackout issue. From 2003 to 2005, she served as Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s first cabinet secretary—Schwarzenegger having improbably ridden into office in California’s historic 2003 recall election. Batjer, whose public service extends from the Reagan-era Pentagon under Caspar Weinberger (her father was appointed to the Nevada Supreme Court by Gov. Paul Laxalt, a close friend and ally of Reagan), to three Republican governors in California and Nevada and now California’s last two Democratic governors, is an experienced hand at the administrative state—who, prior to being appointed head of the CPUC, had no experience in the electric industry.

After several elected officials complained about PG&E’s widespread preventive blackouts, Batjer formally weighed in, writing to the electric utility’s CEO and charging his firm with “failures in execution.” She further warned that PG&E, “created an unacceptable situation that should never be repeated,” while demanding that power be restored within 12 hours in future blackouts rather than 48 hours as is the utility’s objective. She added, “The scope, scale, complexity, and overall impact to people’s lives, businesses, and the economy of this action cannot be understated.” Left out, but implied, were the severe political impacts as well.

But, despite Batjer’s harsh letter, further wind-driven electrical blackouts are likely in the Golden State, with no appreciable precipitation expected for the forests of Northern California for the next month—which isn’t unusual for California’s Mediterranean climate which typically remains dry until the cool rains start in in October or November.

So, how did California’s policies create the conditions that lead to a planned blackout that inflicted $2.6 billion in losses on the state?

There are two main factors involved that, combined, created a deadly dilemma: keep the power on and risk sparks that could set off wildfires, or switch off the power and harm people through lack of electricity. The proximate cause of the dilemma was environmental policies.

First, gross mismanagement of California’s forests and coastal chaparral that discouraged timber harvesting starting in 1994 while also making it difficult to conduct preventive burns, both of which led to a massive, decades-long fuel build up.

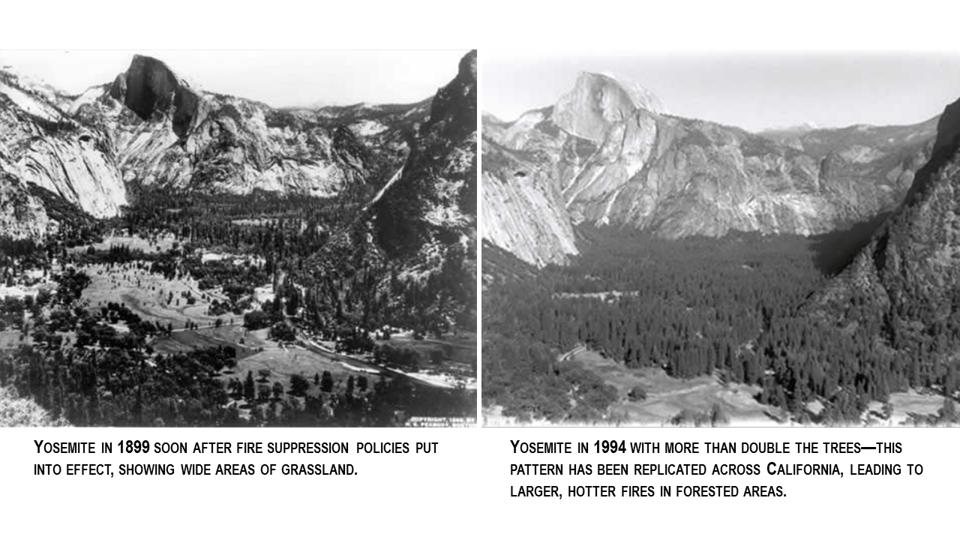

Tree density in California’s Yosemite National Park has more than doubled over the past 100 years, a challenge that has spread to forested areas throughout the state as a lack of forest management and preventive burns has caused a deadly build up in

PUBLIC DOMAIN, CAPTIONS BY THE TEXAS PUBLIC POLICY FOUNDATION

Second, starting in 2002 with a bill supported by the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council and opposed by California’s utilities and trade unions mandated a yearly increase in renewable power by 1% per year, now accelerated to 60% by 2030. This mandate to buy more wind and solar was met with political demands to keep electrical rates down. Ironically, the 70% reduction in natural gas price from 2005 to 2015 due to modern fracking techniques helped mask some of the expenses of going green. But the cost of new power lines to connect vast wind and solar fields with the grid while decommissioning fossil fuel plants with years of life left in them left few additional resources to maintain powerlines.

As powerline maintenance declined and the fuel load under and around the lines increased, the incidence of spark-caused deadly fires mounted.

With PG&E in bankruptcy protection to shield the company from $30 billion in potential claims from 19 major wildfires traced to its equipment in the past two years, preventively cutting power during periods of high winds seemed its only option.

Now California is playing catch up—and it won’t be easy.

PG&E is woefully behind schedule on clearing trees away from 2,455 miles of power lines by year’s end, with only 760 miles completed by September 21.

PG&E says it can’t find crews to do the work—which isn’t a surprise given that a quarter century of anti-logging lawsuits, new laws, and environmental regulation, as well as foreign competition, cut employment in the state’s timber industry in half over the last 20 years, leaving shuttered sawmills, shattered towns and opioid addiction in its wake. Further, clearing trees is hard, dangerous work, with an on-the-job mortality rate second only to commercial fishing.

California’s future is sadly easy to predict: there will be more wildfires in spite of the blackouts. Politicians will alternately blame PG&E, the state’s other power providers, and climate change to shift public anger away from policies they enacted. And, before the last of this fire season’s ash gets flushed into the Pacific there will be a serious attempt at a state takeover of PG&E. Lastly, as is frequently the case when elected officials are taking flak, they may make a scapegoat of their appointees, with CPUC president Batjer likely to be the first on the chopping block at the end of her long career in public service.

Nationally, President Trump may weigh in again on California’s self-inflicted wounds, as he’s done before on wildfires, forest mismanagement and homelessness. In this, California serves as a useful example to the rest of the nation of what progressive policies look like when implemented without regard to the inevitable real-world consequences.